Humans can distinguish a computer-generated image of a human face from the real thing less than half of the time. Worse than flipping a coin.

That’s the finding from a study published earlier this year in the academic journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, confirming just how convincing faces produced by artificial intelligence (AI) can now be.

In that study, more than 300 people were asked to determine whether a supplied image was a photo of a real person or a fake generated by an AI. The human participants got it right less than half the time.

The results of this study will shock anyone who thinks they are switched-on enough to spot deepfakes when they are compared to the real thing.

The Tom Cruise deepfake of the actor playing a guitar which went viral on TikTok last year, brought wide public attention to the increasing sophistication of deepfake technology. So aren’t most deepfakes, like Tom’s, just about entertainment and parody and entertainment, rather than presenting any real threat?

Deepfake harms

A recent study published in a UCL blog post, ranked deepfakes as posing the most serious AI-enabled threat to society, in terms of their potential applications for crime or terrorism.

The UCL authors said deepfake content would be difficult to detect and stop, and that it could have a variety of applications – from discrediting public or political figures to extracting funds by impersonating a relative in distress in a video call. The proliferation of fake video content, the authors argued, could eventually lead to a widespread distrust of audio and visual content of all forms, which itself would be a societal harm.

The technology also has the potential for tremendous damage in the creation of revenge porn or nonconsensual pornography of women. In these cases, fake videos or images don’t have to be all that realistic or convincing to cause real damage.

Although there has been much speculation about the potential harm deepfake technology could cause in politics in particular, so far these effects have been fairly few and far between. But in 2021 European MPs from Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania were allegedly targeted by several deepfake video calls imitating Russian opposition figures.

Those tricked include Rihards Kols, who chairs the foreign affairs committee of Latvia’s parliament. Kols uploaded a photograph of Leonid Volkov, an ally of Navalny, and a screenshot of his doppelganger taken from the fake video call he received. Volkov said the two looked virtually identical. “Looks like my real face – but how did they manage to put it on the Zoom call? Welcome to the deepfake era …” he wrote.

Is the threat overplayed?

However, developers of deepfakes feel their threat is wildly overstated due to the complexity and skill currently involved in creating them which puts them out of the reach of most.

“You can’t do it just pressing a button. That’s important, that’s a message I want to tell people.”

Chris Ume, Belgium VFX specialist

This does ignore of course the fact that AI technology is developing at a relentless pace and that apps like like FaceSwap, FaceApp and Avatarify already exist that enable the public to do a bit of simple deepfakery themselves.

Tips for spotting a deepfake

The FBI issued their first warning related to deepfakes late in 2021 and have highlighted a few useful ways of spotting whether a face in a video is genuine or fake;

- Distortions around the pupils or earlobes of a face.

- Bizarre motions of the head and torso.

- Syncing disparities between the audio and lip movements.

- Background distortions, like indistinct or blurry figures.

- Social media profiles with nearly identical eye spacing throughout a wide spectrum of images.

The most important rule is that where deepfakes are concerned there are no rules. The technology is developing so fast that any tips on how to spot fakes this week could be out of date next. The only way to protect yourself and others is to keep up-to-date with tech developments and news stories and to use basic common sense. If an encounter feels ‘off’ then it probably is. Where deepfakes are involved we all need to keep our guard up.

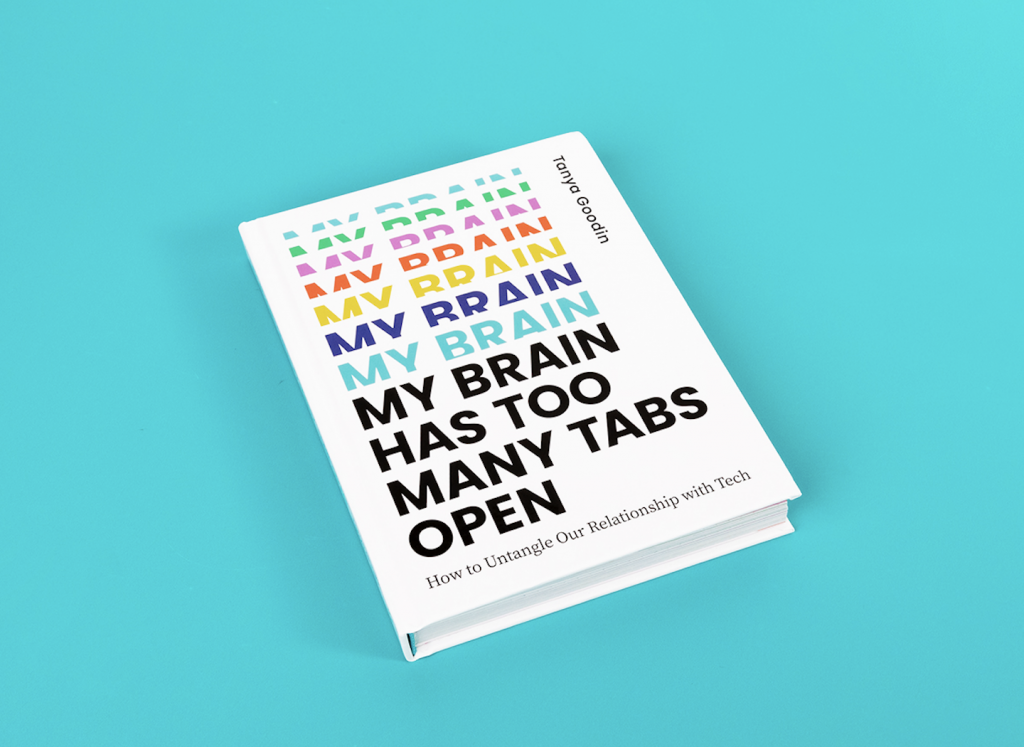

For more about keeping safe online, including dealing with issues around social media and cybercrime – pick up a copy of my new book.