Amazon has had a very good pandemic.

At the end of July, the company announced that it had doubled its Q2 profits to $5.2bn, (v $2.6bn in 2019) with Q3 another blowout, this time with a tripling of profits. All of this before the reporting of the traditionally busy Q4 which includes Christmas, where we can expect sales and profits to have been driven still further skyward.

Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s owner, is now the world’s richest person, with a net worth of $190 billion, (in August 2020 he became, briefly, the first person in history to be worth $200 billion). His personal wealth rose by 65% since the start of the crisis in March 2020 and in just one day in July 2020, he saw his fortune increase by more than £10bn.

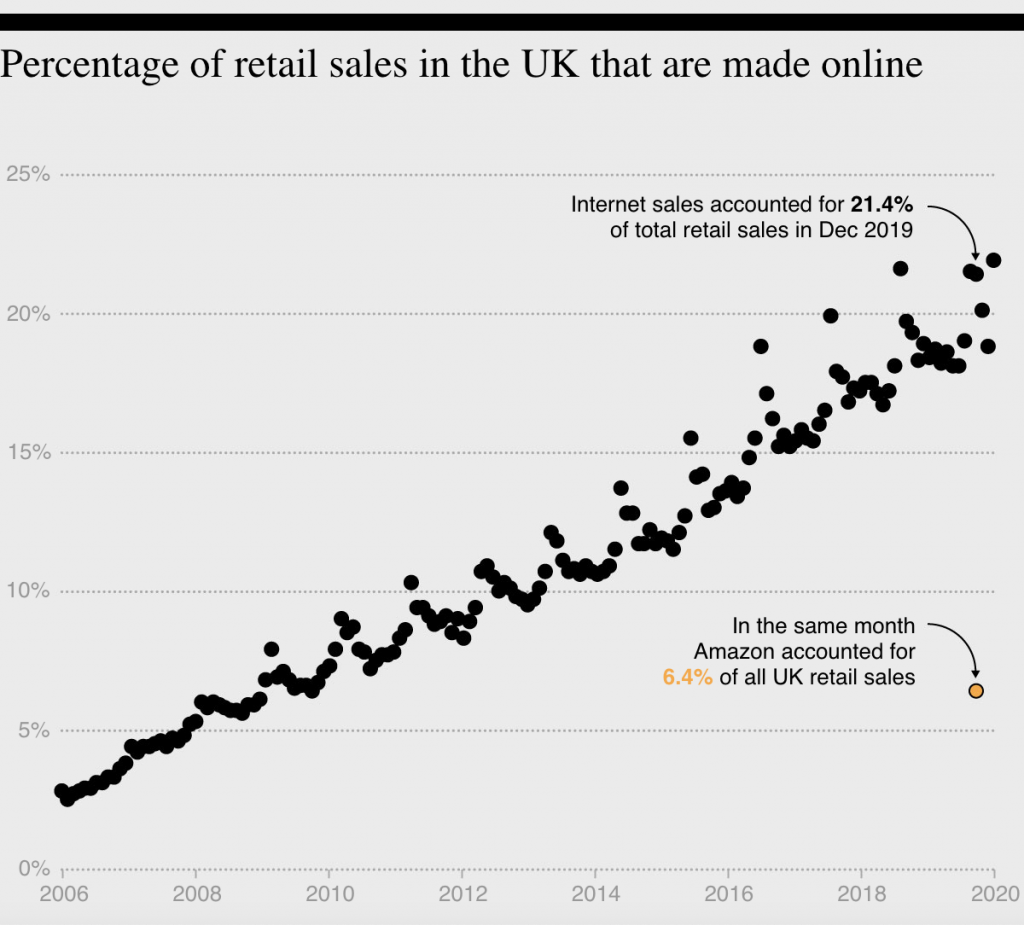

The relentless march of Amazon in taking over every area of our lives has been turbo-charged by the global lockdown enforced by coronavirus. The e-commerce site which started as an online book seller back in 1994, is now the world’s most valuable brand and has expanded into video, web hosting and food delivery, to name just three of its many hundreds of divisions.

Described as “not just a player in the market, it is the market“, it’s difficult to over-state just how dominant Amazon has become globally, and how nigh-on impossible it now is for any other brands or retailers to compete against it.

But of course, Amazon has only grown into the behemoth it is because of our own purchasing habits. When lockdown struck in 2020, consumers all over the world were very glad of the continual flow of brown boxes into their homes which kept their purchases coming. Amazon became seen as a lifeline to those shut-up at home, without too much thought given to how the retail giant was managing to keep the supply going in such challenging times.

The price of convenience?

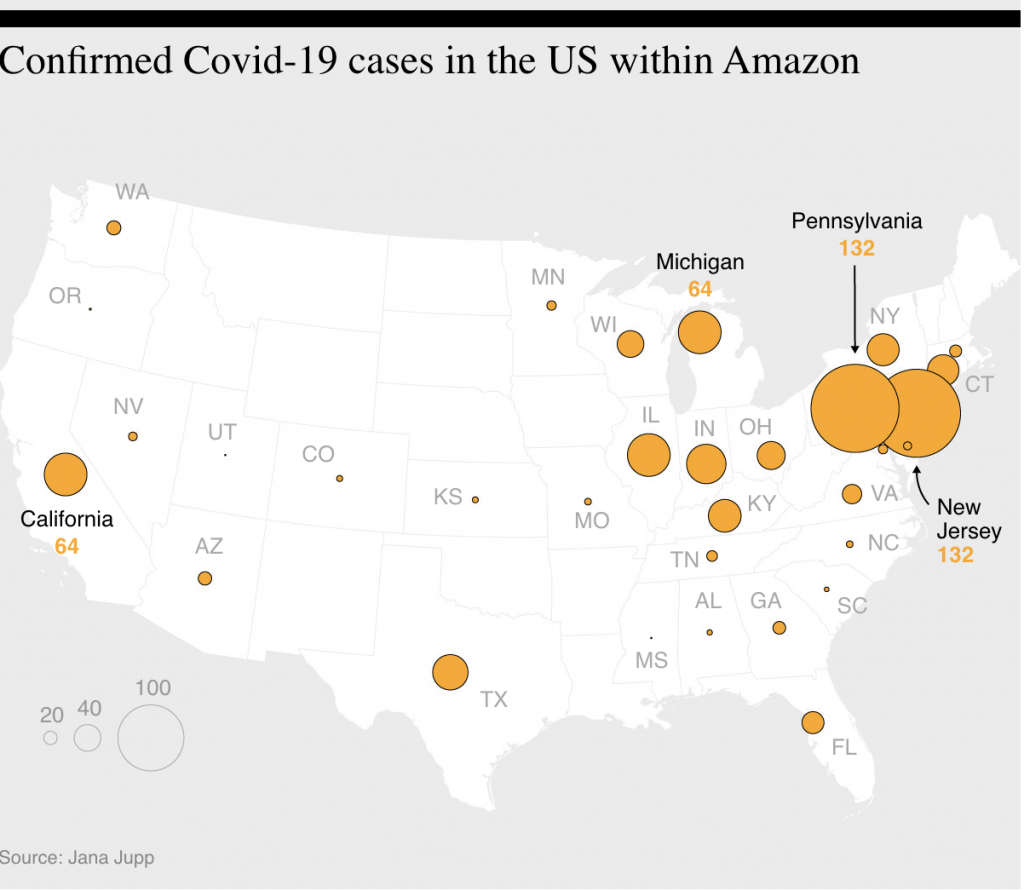

Reports that emerged after the initial UK lockdown, suggest that Amazon’s success may have been at the expense of the health and safety of their warehouse staff. With allegations that ‘pickers’ in UK warehouses were having to average 360 items an hour, or around 3,800 a day (roughly an item every 6.7 seconds) in the boom caused by lockdown, stories emerged of new staff being recruited en masse, crowding into warehouses to keep up with demand and social distancing measures being impossible to maintain.

In the US, a review of lawsuits filed in 2020 against Amazon and messages on social media, paint a picture of complaints about how Amazon behaved during the crisis. Allegations include that the company failed to implement safety procedures early enough; that they disregarded or even retaliated against those raising safety concerns and that they even told employees not to wear masks.

In June 2020 eight Amazon employees were confirmed to have died from Covid-19.

What about the high street?

Meanwhile, as Amazon had its best year ever, retail sales in the UK in 2020 were the worst for 25 years as coronavirus accelerated the move online. Growing numbers of big-name shops faced financial difficulties due to the temporary store closures imposed during lockdowns, and then afterwards due to the reluctance of shoppers to return to the high street when measures were lifted. Topshop owner Arcadia, Debenhams, Mothercare, Edinburgh Woollen Mill, Oasis and Warehouse were just some of the big-name brands who went into insolvency last year. Many smaller and independent retailers that followed suit with one estimate of retail job losses in 2020 put at over 100,000 jobs.

What kind of a retail future do we want?

The ‘death of the high street’ is a topic that has been ringing alarm bells for years, with retailers and consumers alike alarmed at the number of shuttered premises springing up in home towns across the UK, concerned about the heart going out of their neighbourhoods as shopping switches online. But as the nation was forced into lockdown, the humble corner shop emerged as an unlikely hero and a lifeline for local communities with many rediscovering the retailers on their doorsteps and singing their praises for how they helped them survive.

The mini-boom of local shopping benefitted communities throughout 2020, but as consumers we now find ourselves at a crossroads when we stop to consider what kind of a shopping future we want. The pandemic has given us a unique glimpse into two alternative future scenarios; on the one hand the speed and convenience of never having to leave our homes to visit shops again; on the other hand the rediscovery of the local independent retailers, who have always acted as the focus point for our communities and enabled everyone in them to feel connected.

Usually in the digital v offline debate the benefits of the latter over the former are intangible and difficult to define. But the pandemic has given us a very clear view of where we are potentially heading if our Amazon shopping habits continue unabated. Do we want our lives to be dominated by just one company at the expense of local communities? Or do we want to make deliberate and informed purchasing decisions that may enable us to put money back into our neighbourhoods?

Like so much of this debate, the power really is with us as consumers.